Productivity provides a simple but powerful indicator of a country, sector, or company’s ability to use its resources optimally to drive growth.

Productivity is defined as the efficiency of production. It is the ratio of production output to input.

Different dimensions can measure productivity growth:

- Labor productivity

- Total Factor Productivity (hereinafter TFP)

Labor productivity measures output per employed worker or, if working hours can be measured (mostly only in mature economies), output per hour worked. At country level, output is typically measured as the economy’s Gross Domestic Product (at sector level called value added) adjusted for inflation. Labor productivity growth represents a higher level of output for every hour worked. Labor productivity is a key dimension of economic performance and an essential driver of changes in living standards.

The Total Factor Productivity is a more sophisticated metric. It measures the change in output relative to change in labor and capital. It is a better measure of productivity than labor productivity because it assesses the efficiency with which both these inputs are used. Broadly defined, TFP can be taken as an indicator of an economy’s long-term technological progress. Improvements in managerial capabilities, organizational competence, research and development, resource allocation, and technology diffusion all contribute to TFP growth.

The necessary precondition required to start this research is related to problems with official Chinese economic data and statistics. Issues include structural breaks in employment statistics, implausibly high labor productivity figures relating to “non-material” services, serious inconsistencies between output measures in industrial statistics versus those in national accounts, as well as between volume movements and changes in real values. There are also conceptual flaws in official measurements of fixed-asset investments and biases in the prices of the investments. For these reasons, productivity data frequently differ in accordance with the sources they are derived from. From several studies clearly demonstrate how overall pace of GDP growth in China has been systematically overstated since 1978, during a period called the “reform era.” In addition to the overestimation of GDP growth there are high estimates of productivity growth rates that apparently characterize China during this period. These studies reveal how these growth trends should be properly interpreted and managed. The quality of China’s post-reform growth has been the subject of heated debate in literature. The center of the debate is whether China’s growth over the reform period is significantly attributed to productivity growth or mainly driven by factor accumulation.

Looking more deeply at China’s economic situation in the last century, as Mr. Hu has done by re-estimating Chinese productivity in a more reliable way, China’s eventual failure to progress its productivity is revealed. In fact, the Chinese economy’s productivity performance since 1952 shows that the country’s capital-intensive development has come at the expense of efficient resource allocation, even during times of great institutional change that were previously thought to enhance productivity. Thus, China’s economy, once described as miraculous, is now struggling with rapid wage increases and a declining number of new workers, so productivity gains increasingly must come from structural reform, automation, greater company efficiency, and innovation.

By 1979, China has risen to middle-income status primarily by exploiting labor cost advantages. These advantages vanish once the pool of surplus labor is exhausted and wages start to accelerate. After decades of rural migration to urban centers creating a concomitant steady and growing supply of low-cost labor, the numbers have been trending downward—rapidly. Wages in China have been rising faster than GDP.

Another cause of the rapid productivity rate increase could be the low point it started from.

After a brief general introduction, the research begins to reveal the ongoing ‘soft fall’ slowdown in Chinese economic growth despite the government’s continued stimulus exercises and high levels of investment and supporting credit expansion. It is natural for growth to slow as economies mature, as predicted by growth convergence theories. Low economic growth can be associated with low productivity growth.

At 7 percent annual labor productivity growth in 2013, the official estimates of output and employment suggest that China continues to show one of the highest labor productivity growth rates in the world, which has made it by far the largest contributor to overall global productivity growth. Recent independent analysis by The Conference Board (January 2014), however, shows that China’s actual output and productivity growth rates could be substantially lower, putting it at only 3.9 percent for output and 3.6 percent for labor productivity in 2014. However, regardless of the metric employed the key factor is that Chinese productivity growth has shown a declining trend for several years now—even officially— from almost 9.5 percent average during 2007-2012 to 7.3 percent in 2012 and 2013 and 7 percent in 2014, which is the lowest productivity growth the Chinese economy has experienced during the last decade.

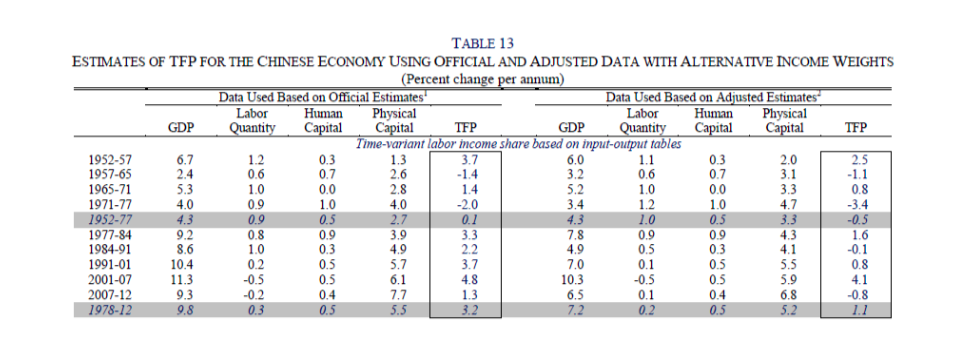

Adopting the TFP perspective and using the adjusted data provided in the aforementioned analysis by The Conference Board, we see how in terms of TFP—as a measure of an economy’s technological dynamism—

China badly lagged behind other Asian high-growth economies at a similar stage in their development. China’s 1% average annual growth in total factor productivity between 1978 and 2012 compares to 4% annual gains for Japan during its comparable 1950-1970 high-growth period, 3% for Taiwan from 1966-1990 and 2% for South Korea from 1966-1990.

The only period that saw a significant TFP growth was the one following China’s WTO entry, from 2001 to 2007. After that, the economy was impacted by the global financial and economic crisis. In this period, China benefited from its comparative advantage in labor-intensive manufacturing through a substantially enlarged world market. China suddenly found itself in a very competitive position because they had built up a huge production capacity in the previous decade that was significantly underutilized (evidenced by China’s persistent deflation from 1998 to 2002).

However, China’s WTO entry promoted productivity not only because it allowed China to benefit more from its comparative advantage, but it also speeded up China’s learning-by-doing process through deeper and wider international market exposure as well as institutional reforms prompted by such exposure. Below is the table with either the data based on official estimates or those adjusted by research.

The economic growth slowdowns are often associated with significant slowdowns in total factor productivity (TFP) growth. On average, more than three quarters of the slowdown in the growth rate of output are explained by the slowdown in TFP growth. Productivity slowdowns can be associated with difficulties moving up the value chain, away from factor accumulation to an innovation-driven growth path.

Given the current situation of economic growth and productivity slowdowns, China is being called to action in order to boost its declining pace of productivity. There are many key areas in which China could intervene and develop strategic actions. These areas are not mutually exclusive, thus China can make improvements in different aspects at the same time. China, having reached high levels of factor accumulation-led growth, needs diversification into higher value-added sectors within agriculture, industry, and services. It would increase overall economic productivity.

Regarding innovation, one of the key drivers of productivity, China has already gained an advantageous position compared to many others countries. In fact, its increasing GDP share of imports of foreign technologies through capital goods and inward FDI has allowed the development of local capabilities and has led to productivity improvements. China had the most significantly imported capital goods during the last decade. The importance of foreign knowledge embodied in imported products and acquired through FDI is notable even observing the higher productivity of partly- or fully-owned enterprises rather than the productivity of local firms. China has made great progress in the last decades: it was the second largest spender on R&D in the world in 2011.

Part of China’s success in tapping global knowledge is its massive investments in technical human capital accumulation. However, in the immediate term, China must focus on getting more from the existing labor force. This means improving labor mobility and reducing skills mismatches in the workforce. A first step to boosting productivity is to reform the country’s household registry system, known as hukou. It was originally established by the government to limit the influx of people from the countryside, as well as movement between cities. But hukou has ended up costing the country in terms of productivity by imposing barriers to labor mobility.

With regard to the workforce a better match between skills demanded and skills supplied is needed.

Nowadays there are too many Chinese graduates from universities with only theoretical knowledge, and too few people have the vocational skills that appeal to employers. To improve the situation the Chinese Government is working hard to develop education systems responsive to the needs of productivity-driven economies. For instance, through vocational training tends to produce more productive employees.

Productivity also depends on the company’s size, as larger firms tend to be more productive than smaller firms. Pursuing mergers and acquisitions to drive scales of economy and add value through creative partnerships would be a source of improvement in productivity.

One more relevant action plan should aim to boost productivity and efficiency in service industries. It would have great potential as a way to enhance overall economic competitiveness, particularly in developing countries where services are generally less developed relative to their per capita incomes, as in China. A manufacturing-based economy such as China has significant room to catch-up by fostering services that offer a high potential for productivity gains.

Another important step has been China’s Western Development Strategy initiated in 2000. The main goal consists in the convergence of productivity. In such a big country, a better distributed level of productivity helps foster the overall economic condition in the long term.

Undoubtedly, productivity is a key factor on the government agenda. China’s leaders recognize the importance of productivity to China’s economic future. A key objective of the 12th five year plan (2011-15) has been the general will to shift the growth pattern towards consumption-led, efficiency-focused growth. Companies are thus facing increasing pressure to raise productivity in coming years. Industrial policy will incentivize improvements in productivity and increasingly penalize unproductive and wasteful companies. Companies must therefore view productivity as a strategic imperative. For the economy as a whole, more productivity growth will come from improvements at firm level. Companies will need to dramatically improve their internal processes to deliver products or services with fewer inputs. They are advantaged by the chances that the structural changes will create in the future, such as the reforms designed to lower market barriers and the opening up of new industries to investment.

Overall Chinese productivity is on a declining path, as rapid falls in the efficient use of capital and the returns on capital are having adverse effects. This clearly suggests that China can climb the value chain only by focusing on higher productivity activities through technological change and innovation. In particular, relying on technology could maximize efficiency gains. Either maximizing the benefits of information technology or exploiting technological catch-up by combining different existing technologies and adapting them for China’s needs will boost growth and productivity, improving China’s macroeconomic condition and the real wealth of people. However, the results of those efforts typically require a significant time to materialize.

References

- Perspectives on Global Development 2014, OECD

- The Conference Board Total Economy Database, Summary Tables, May 2015

- China’s Growth and Productivity performance Debate Revisited – Accounting for China’s Sources of Growth with a New Data Set, Harry X. Wu. Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo. January 2014.

- China’s productivity imperative, Ernst&Young, 2012

- Productivity Brief 2015, Global Productivity Growth Stuck in the Slow Lane with No Signs of Recovery in Sight, The Conference Board Total Economy Database

- The view from China productive frontier, Accenture, 2013

- China’s Productivity Problem Drags on Growth, MARK MAGNIER, 2014

- Labour Productivity, The Economist, 2013

- OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2015